Particular attention must be paid to the phenomenon of polysemy in translation of a chemistry patent application. When a word can be translated in more than one way, all the translations may be acceptable, but in most cases, only one of them is technically reasonable.

Here is an example. The Japanese expression “接着性” (meaning “adhesiveness”) may be translated into either “粘接性” or “粘附性”, neither having essential effect on the interpretation of the concerned technical solution and thus being available for option by the translator.

In most cases, however, only one translation is acceptable although a word can be literally translated in several ways. For instance, “接触酸化” (literally meaning “contact oxidation”) may be translated into “

接触氧化,” but this translation is not accurate with respect to chemical engineering, and the correct translation is “

催化氧化” (meaning “catalytic oxidation”). This example tells us technical dictionaries and applicants’ confirmation are necessary for a translator to avoid the mistake of word-to-word translation.

Some of the most common terms in the filed of chemistry which correspond to various translations include:

(1) “酸素” may be translated into “氧气” (meaning “oxygen gas”) or “氧” (meaning “oxygen”);

(2) “ベンジル” may be translated into “苄基” (meaning “benzyl” with a molecular formula C

6H

5CH

2-) or “苯偶酰” (meaning “benzyl” with a molecular formula C

14H

10O

2);

(3) “分散” can be translated into “分散” (meaning “dispersion”) or “色散” (meaning “chromatic dispersion”).

If an inappropriate translation is adopted for such a term, a misunderstanding of the technology involved in the patent application will arise, which may result in complications in subsequent procedures.

B. One sentence with several potential translations

Similar to polysemy, a Japanese sentence may be construed in several ways.

To illustrate the point under discussion, we give an example. Of the sentence “窒化アルミニウム焼結体よりなる基材と高融点金属部材

からなる積層体の製造方法”, “…からなる” can be translated into “由…组成/形成” (meaning “consisting of”) or “包含/包括…” (meaning “containing/comprising”). The former is a “closed” translation, meaning “comprising only,” while the latter is an “open” translation, meaning “comprising some other substances (steps) in addition to….” In this case, the attorney must technically determine which translation is correct. To be specific, if the laminated body comprises only a “substrate material” and a “high melting point metal member,” then the former translation is correct; if the laminated body also comprises, for example, a “protective layer,” in addition to a “substrate material” and a “high melting point metal member,” then the latter translation is correct.

In brief, to have a correct translation, the relevant technology has to be considered when a sentence can be interpreted in more than one way.

C. Ambiguous sentence meaning

Example 1: 未加硫の該ゴム組成物のチューブをマイクロ波加硫装置内で、ゴム押出し装置から連続して押出す.

This sentence was initially translated into “在微波硫化装置内,从橡胶挤出装置连续挤出未硫化的该橡胶组合物的管” (meaning “In the microwave vulcanization apparatus, tubes made of the unvulcanized rubber composition are successively extruded from the rubber extrusion apparatus”). In fact, the correct translation is that “从橡胶挤出装置连续挤出未硫化的该橡胶组合物的管,所述未硫化的橡胶组合物管被输送到微波硫化装置内” (meaning “Tubes made of the unvulcanized rubber composition are successively extruded from the rubber extrusion apparatus, and then conveyed into the microwave vulcanization apparatus ”).

To correctly translate the above sentence, the attorney must know whether the operation of “連続して押出す” is conducted in “マイクロ波加硫装置内で”. At the first glance, the operation seems to be conducted in the vulcanization apparatus. Technically speaking, however, it is logical that the tubes are first extruded from the extrusion apparatus, followed by being

conveyed into the vulcanization apparatus.

In the correct translation, the word “输送至” (meaning “conveyed into”) is actually added by the translator. We draw an inspiration from this example that when a patent attorney encounters a Japanese sentence having no explicit meaning, he must consider other contents in the specification and the drawings; if this still disables the attorney to determine its meaning, he must consult the applicant. On the other hand, the above example reminds the applicant not to omit verbs or subjects of sentences in drafting claims.

Example 2: 結晶で構成される酸化タングステンを含む…

The attorney translated the sentence into “包含由结晶形成的氧化钨的…” (meaning “… containing a tungsten oxide formed through crystallization…”). Such a translation is exactly faithful to the original, meaning “酸化タングステンは結晶で構成される”, but it connotes that the tungsten oxide contains no amorphous part, as opposed to the fact that the crystalline tungsten oxide coexists with the amorphous part. To avoid the divergence between the original and the translation, it is better for the drafter of the application to write the sentence as “結晶構造を有する酸化タングステンを含む…”

As shown above, it is unavoidable that a Chinese attorney and an applicant/inventor have different interpretations of a sentence in Japanese, because the attorney is liable to consider grammatically while the applicant/inventor is more flexible in expressing himself. Such being the case, it is likely that a translation is correct grammatically but wrong technically. To eliminate this problem, efforts from both sides are needed, with the attorney considering the specification as a whole and the drafter avoiding ambiguity.

D. Incorrect pauses in sentence interpretation

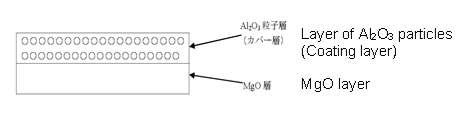

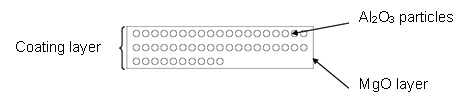

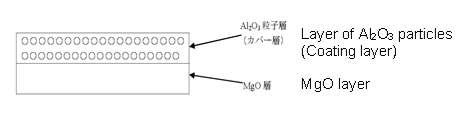

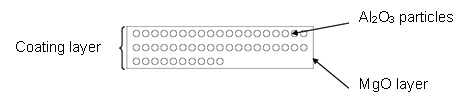

Example 3: MgO層上に微細なAl2O3粒子を有するカバー層とすることができる

This sentence can be literally translated into “在MgO层上

可制成具有微细的Al

2O

3颗粒的覆盖层” (meaning “to form a coating layer of fine Al

2O

3 particles on the MgO layer”) or “

可制成在MgO层上具有微细的Al

2O

3颗粒的覆盖层” (meaning “to form a coating layer in which fine Al

2O

3 particles are on the MgO layer”). To understand the technology, see the drawings below:

Fig. 1 (corresponding to the former translation)

Fig. 2 (corresponding to the latter translation)

Based on the actual technology, the latter translation is correct.

E. The same katakana but different English words, creating different Chinese translations

To illustrate this problem, one example includes, “グロウボックス” which may mean “glow box” or “grow box” according to its pronunciation. If the attorney is not certain which one is correct, he needs the applicant’s confirmation.

Because of the pronunciation characteristics of English and Japanese, a katakana word generally represents several English words, thus blinding the attorney to find its true meaning, especially when the meaning is hard to deduce from the specification. To solve this problem, one of the most effective ways is for the applicant to indicate in advance the correct English for katakana which sounds variously.

F. Points to pay attention to in chemical naming

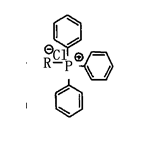

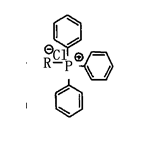

“トリフェニルホスホニウムクロリド” can be literally translated into “氯化三苯基膦”(meaning “triphenylphosphine chloride”) or “三苯基氯化膦”(meaning “triphenylchlorophosphine”). The former translation, however, seems inappropriate because it does not indicate whether the chlorine atom is attached to the phenyl group or to the phosphorus atom. On the contrary, the latter translation is correct, making it clear that chlorine atom is attached to the phosphorus atom.

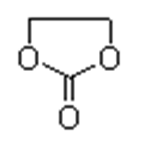

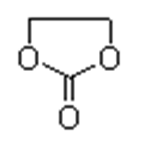

Here is another example. “エチレンカーボネート” can be literally translated into”“碳酸乙二酯” ,“碳酸亚乙酯”or “碳酸乙烯酯”, but according to the structural formula of the compound (see below), the last translation is wrong.

The foregoing is no more than a general understanding of translation of chemistry patent applications. With technological progress, new words will come in flocks, increasing various problems in translation for attorneys. This requires attorneys dealing with foreign applications to always discover problems and accumulate experiences in daily work. It is hoped that this paper is a bit helpful to readers.