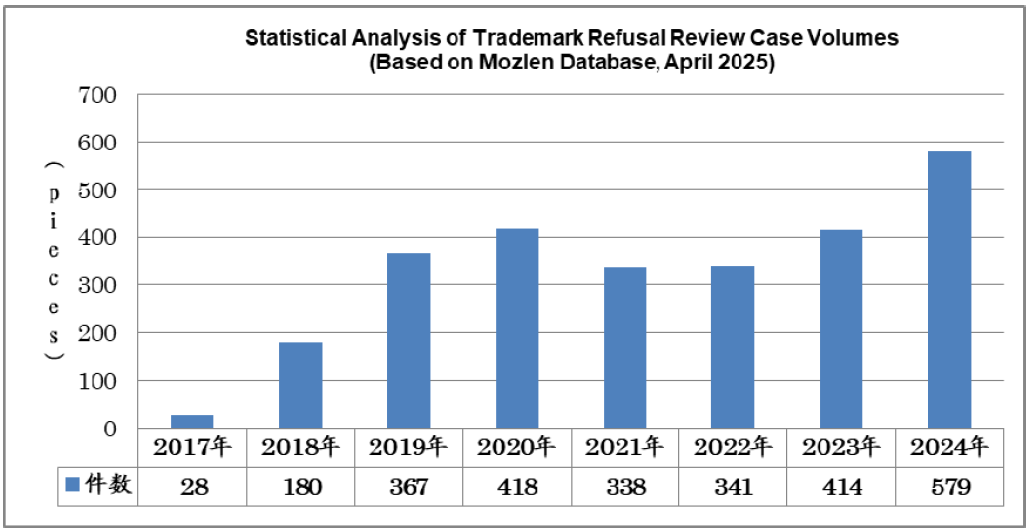

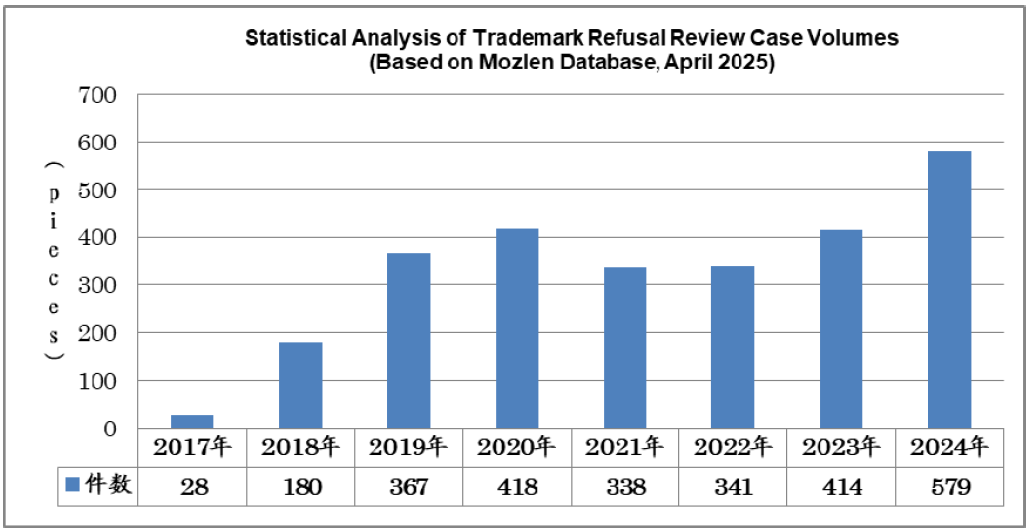

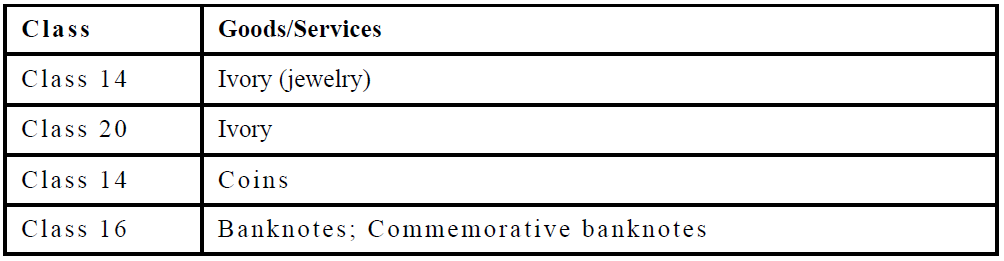

In the context of globalization, the Madrid International Trademark Registration System provides global enterprises with an efficient, convenient, and cost-effective channel for trademark protection when entering the Chinese market, making it a crucial option for pre-entry trademark strategy. However, in practice, unlike domestic trademark applications in China, international trademarks seeking territorial extension protection in China often face refusals not only due to conventional grounds like conflicts with prior rights but also frequently encounter challenges under Article 22 of China’s Trademark Law for non-compliant goods/services that deviate from Chinese standards. Domestic applications are able to avoid such issues due to the formality examinations on goods/service conducted prior to the application acceptance. As demonstrated by the author’s statistical analysis of Mozlen data in the table below, refusal review cases related to Madrid international trademark registrations citing Article 22 have been steadily increasing, highlighting this issue as a “unique challenge” for overseas enterprises opting for international trademark registration.

The author has also observed that while the number of such refusal cases continues to rise, the scope of affected goods/service classes is expanding significantly. The refusal review cases in early stage predominantly focused on Class 35, stemming from China’s historical non-acceptance of wholesale and retail services except for pharmaceuticals and medical supplies. In recent years, refusals involving this provision have expanded to multiple classes, covering emerging fields such as new technologies, virtual goods, and healthcare. A recent typical case handled by the author involved an international trademark seeking territorial extension protection across nearly forty classes in China, where nearly half of the classes were rejected due to the non-compliance of its designated goods/services with Chinese standards. This case underscores the persistent challenge of compliance of designated goods/services in international trademark extension protection, serving as a wake-up call for global applicants. This article aims to identify common “minefields” of the non-compliance of designated goods/services in China’s territorial extension and propose targeted recommendations to help international trademark applicants mitigate such risks proactively.

I. Common “minefields” of the non-compliance of designated Goods/Services in China’s Territorial Extension Protection for International Trademarks

Based on the analysis of recent refusal review cases and practical experience, the circumstances of the refusal of international trademark applications seeking territorial extension protection in China due to non-compliance of the designated goods/services with the Chinese standards could be categorized into the following four types:

1. Goods/Services Incompatible with China’s National Conditions

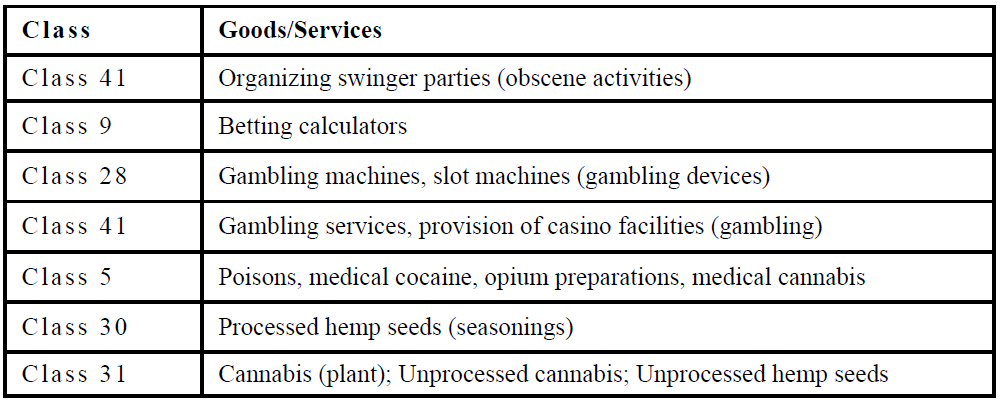

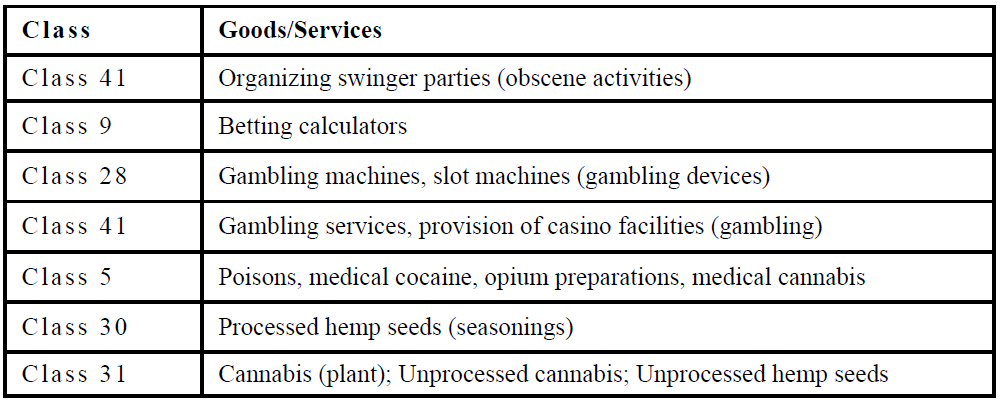

Goods/services deemed incompatible with China’s national conditions generally include the following three types:

(1) China does not accept applications for goods/services related to “

pornography”

(obscene content, etc.), “

gambling”, or “

drugs” (

e.g., narcotics, etc.).

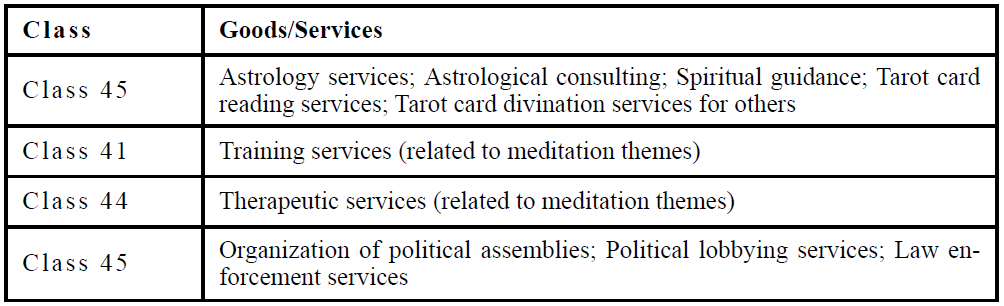

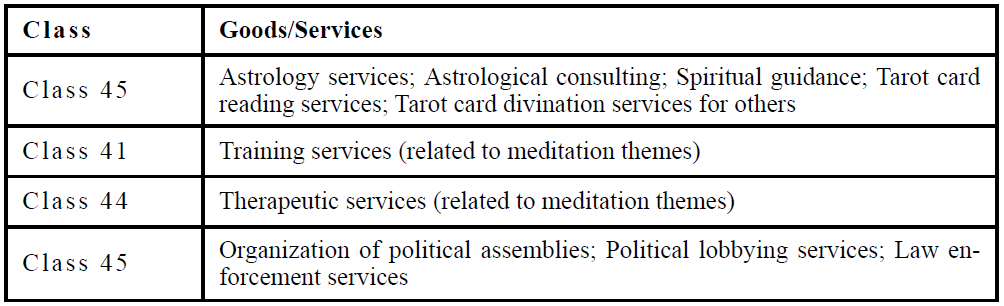

(2) Related to feudal superstition or political activities in sensitive/prohibited sectors.

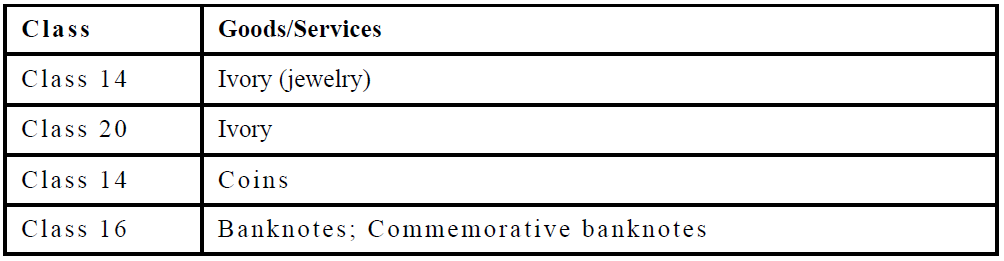

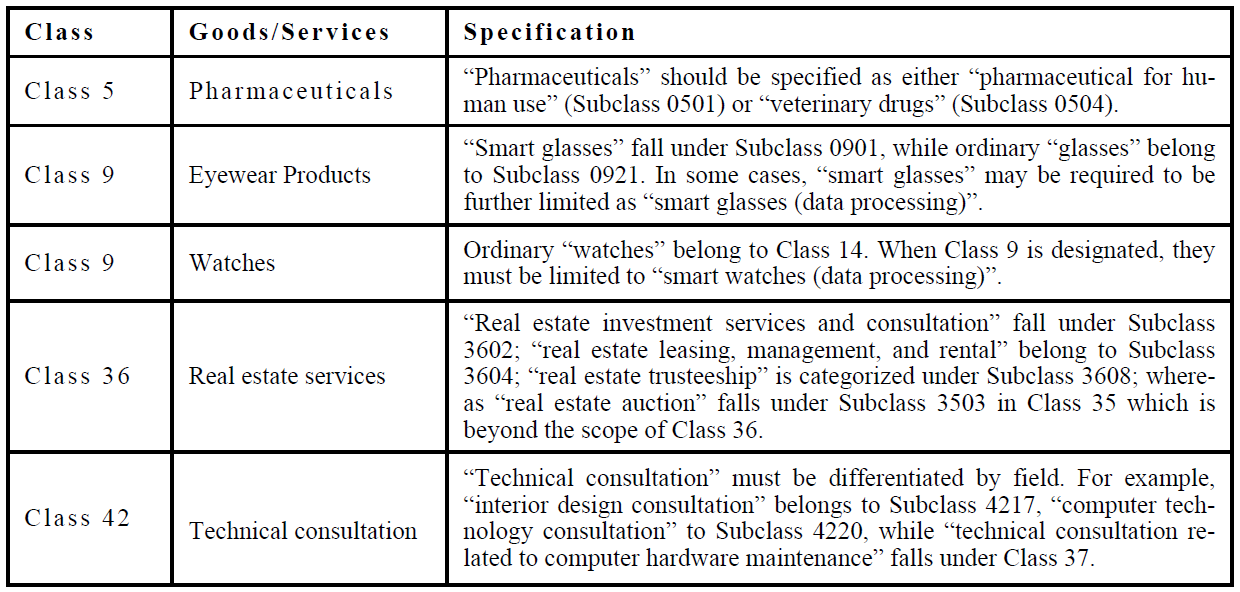

(3) The Goods prohibited for trading in China (e.g., products derived from protected wild animals, currency)

2. China’s Prudential Examination on Emerging Sectors

2. China’s Prudential Examination on Emerging Sectors

China currently does not accept goods/services related to cryptocurrencies, digital tokens, virtual assets, etc. The designated goods/services specifications containing particular terms such as “crypto currency” or “non-fungible tokens (NFTs)”, “downloadable software for generating cryptographic keys for receiving and spending crypto currency” in Class 9 or “clothing authenticated by non-fungible tokens (NFTs)” in Class 25—will not be accepted by Chinese trademark examination authorities.

Meanwhile, although China’s current (2025)

Classification Table of Similar Goods and Services (hereinafter the “Classification Table”) and the CNIPA’s periodically published list of acceptable goods/services beyond the Classification Table include a number of goods/service descriptions containing the term “virtual,” the CNIPA maintains strict scrutiny over goods/services incorporating “virtual” terminology in trademark examination practice. In multiple refusal review decisions involved Chinese part of international trademarks (e.g., International Registrations No.G1765748, G1760041, G1760051, G1763840, G1748449), the CNIPA has explicitly stated its current refusal tendency towards the goods/services related to the metaverse or virtual concepts. Examples include “downloadable virtual clothing” in Class 9 and “online banking services rendered in virtual environments” in Class 36, both of which are the terms officially stated unacceptable in an explicit manner.

Additionally, as the particular terms such as “crypto currencies,” “non-fungible tokens (NFTs),” “metaverse,” and “virtual” possess cross-industry applicability and can describe goods/services across nearly all classes, goods/service descriptions incorporating such terms may appear in all 45 classes. This has become the primary reason for the continuous expansion of classes determined as not complying with China’s standards in the international trademarks seeking territorial extension protection in China in recent years.

3. Increasingly Stringent examination on Goods/Services Specifications

From Chinese trademark examination practices, the China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA) has historically adopted a more lenient approach toward goods/services specifications in international trademark territorial extension applications compared to domestic applications. For instance, broad specifications such as “attachments and parts for XX goods” spanning multiple subclasses were generally acceptable. However, recent examination trends indicate a tightening of these standards, with a growing number of refusal cases where the goods/services specifications span multiple classes or multiple subclasses. In practice, common non-compliant scenarios primarily fall into the following three categories:

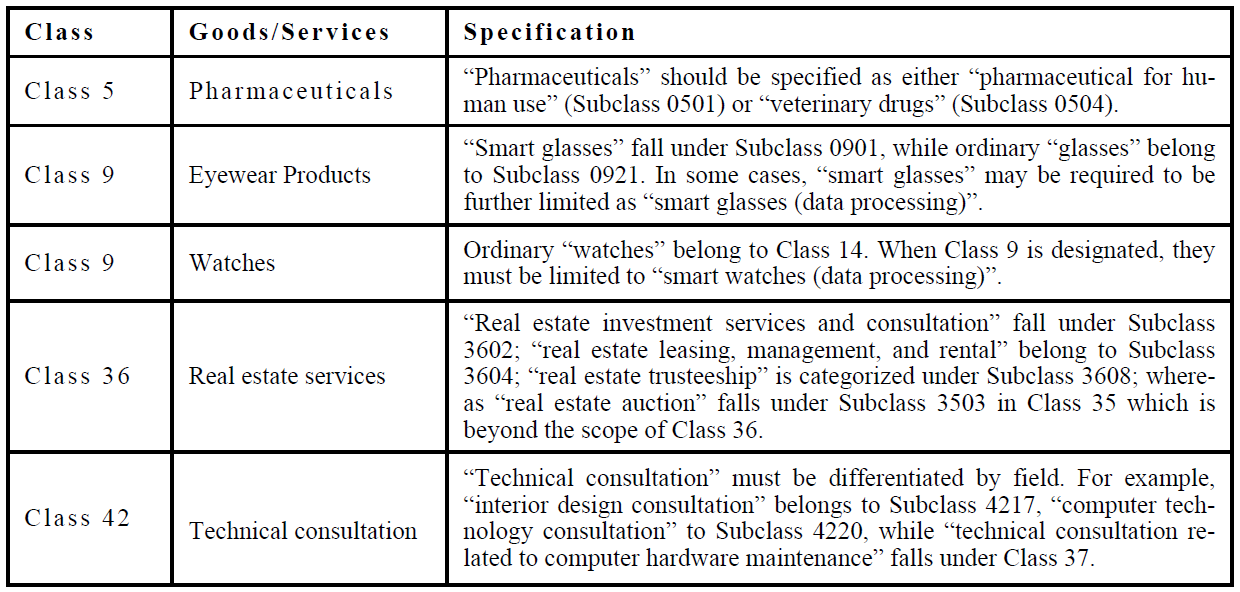

(1) The goods/services specifications crossing multiple classes or multiple subclasses require further restriction.

(2) The specifications that were used to be standard in

China’s Classification Table of Similar Goods and Services but were deleted during classification revisions are no longer accepted in international trademark examinations and must be limited to specific goods.

In practice, typical examples include Class 1 “Industrial Chemicals” (deleted in 2023, originally covering all 20 groups under Subclass 0104) and Class 28 “Game Apparatus” (deleted in 2024, originally covering two groups under Subclass 2801). Since China’s current

Classification Table of Similar Goods and Services has removed these general descriptions without adding equivalent replacements, applicants must specify detailed goods. For instance, Class 28 “Game Apparatus” can be revised to “video game machines” under Subclass 2801(1) and “amusement park ride toys” under Subclass 2801(2) to cover the rights scope of all the groups under Subclass 2801. However, for Class 1 “Industrial Chemicals,” which originally covered all 20 groups under Subclass 0104, it is now impossible to cover all groups by specifying a few individual goods based on the current Classification Table. Applicants need to designate the specific chemical products based on their actual business, such as “textile finishing chemicals” under Subclass 0104(1) or “concrete aeration chemicals” under Subclass 0104(2).

(3)The goods/services specifications containing special functional or efficacy-related descriptions must be deleted as they do not comply with China’s examination standards.

Typical examples listed in the

Comparative Table of Similar Group Codes for Goods and Services in China, Japan, and Korea (Nice Classification NCL12-2025 Text) include “dietary supplements

with beautifying effects” under Class 5 (medical efficacy descriptions) and “

clothing containing weight-loss substances” under Class 25 (functional descriptions).

4. Restrictive Acceptance of Wholesale/Retail Services (Class 35)

Under current Chinese trademark examination practice, wholesale and retail services (Class 35) are only accepted for pharmaceuticals and medical supplies. In practice, the refusal of international trademarks due to the designation of non-pharmaceutical wholesale/retail services in Class 35 is among the most common “minefields” for non-compliance with Chinese standards. Foreign applicants should note that for non-pharmaceutical wholesale/retail services, they may refer to

Classification Table of China’s Similar Goods and Services and adjust specifications to the specific items that are acceptable under Subclass 3503, such as “sales promotion for others,” “procurement services for others [purchasing goods and services for other businesses],” “provision of an online marketplace for buyers and sellers of goods and services,” or “promotion of goods through influencers.” These standardized descriptions help maximize protection scope while adhering to China’s examination standards.

II. Recommended Strategies

For the aforementioned goods/services items that do not comply with Chinese standards, and in light of the current acceptance standards for goods/services under Chinese trademark examination practices, the following targeted strategies could be adopted when applying for the extension of protection (territorial extension) in China:

1. China adopts stringent criteria in trademark examination for goods/services involving the country’s specific national conditions. Any form of wording modification is unlikely to gain approval. In practice, it is advisable for international trademark applicants to directly remove such items when designating territorial extension protection in China. Specific reference could be made to the goods/service specifications marked as “Not Accepted in China” or “X” in the Comparative Table of Similar Group Codes for Goods and Services under the Nice Classification for China, Japan, and South Korea (published in 2020 with annual updates) issued by the CNIPA. This helps prevent application obstacles caused by non-compliant items that conflict with China’s national conditions.

2. When designating China for territorial extension protection in international trademark applications, particular caution should be exercised for goods/services in emerging technology fields. Currently, Chinese trademark examination explicitly refuses applications involving cryptocurrency, digital tokens, virtual assets, and related derivative goods/services. Applicants must strictly avoid particular terms such as “cryptocurrency,” “Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs),” and “metaverse” in their goods/service specifications. Additionally, the term “virtual” is considered highly special and should be used with extreme caution unless explicitly accepted in the official classification guidelines.

Moreover, given the inclusion of “blockchain technology” related service items in China’s current Classification Table of Similar Goods and Services (e.g., Class 36: “electronic funds transfer provided via blockchain technology” and Class 42: “user authentication services using blockchain technology”), applicants may consider adopting “blockchain technology” to limit the emerging goods/services. This approach aims to secure the broadest possible protection scope while complying with China’s standardized requirements for goods/service specification.

3. Under China’s increasingly stringent trademark examination background, international trademark applicants are advised to narrow down broad descriptions of goods/services that may cross multiple classes when designating China for territorial extension protection. Additionally, applicants should strictly avoid including characteristic descriptions of special functionalities or effects in their goods/service specification, so as to mitigate refusal risks arising from non-compliant description.

4. Currently, China adopts a restrictive acceptance policy for trademark examination of wholesale and retail services, only accepting services related to pharmaceuticals and medical supplies. For non-medical wholesale and retail services, as mentioned above, applicants can adjust the relevant services to acceptable specific services under Subclass 3503 in Class 35, in accordance with their actual services, referring to the Classification Table of Similar Goods and Services.

Additionally, if an international trademark faces refusal during its territorial extension designation in China due to non-compliant specification of goods/services under Chinese standards, the overseas applicant may simultaneously take two actions: (1) file a refusal review petition with the CNIPA through a domestic agent, and (2) submit a limitation request (limitation/MM6) to the International Bureau to delete or modify non-compliant goods/services items—for example, adjusting them to align with standardized descriptions in

China’s Classification Table of Similar Goods and Services—thereby to overcome the grounds for refusal. The modified goods/services specifications must not exceed the scope of rights under the original international registration in principle. While Chinese authorities generally apply a relatively flexible approach in determining whether the modified goods/services expand beyond the original scope of rights, there have been cases where limitations were rejected due to exceeding the original scope of rights. Therefore, it is advisable to cautiously evaluate any adjustments to the specification to avoid adverse impacts on the final approval resulting from excessive modifications.

III. Conclusion

The standardization requirements for goods/services items by China’s trademark examination system serve as a critical criterion for obtaining extension of protection in China through the Madrid international trademark registration. Overseas applicants, particularly those in emerging technology sectors, are advised to keep a close eye on evolving practices in Chinese trademark examination and adopt precise and strategic formulations of goods/services specifications to maximize the scope of protection while ensuring compliance with China’s review standards.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————-

References:

International trademark refusal review decisions (2017–April 2025) from the Mozlen Database as of April 2025.

The Comparative Table of Similar Group Codes for Goods and Services in China, Japan, and Korea under Nice Classification (2020–2025).