Linda Liu & Partners

Abstract

In April, 2009, CHINT Group Corp. (hereinafter referred to as “CHINT Group”) settled its patent infringement suit against Schneider Electric Low Voltage (Tianjin) Co., Ltd. (hereinafter referred to as “Schneider Electric”). CHINT Group sued Schneider for infringement of its utility patent No. 97248479.5 (hereinafter referred to as “patent at issue”). Prior to the settlement, CHINT had been awarded RMB 330 million by the court of first instance, which is the largest amount ever awarded in a patent infringement dispute in China. This case was settled three years after the commencement of the action.

Schneider Electric responded to CHINT Group’s suit by immediately filing a request for invalidation of the patent at issue with the Patent Reexamination Board, on the grounds of insufficient novelty, inventive step, and disclosure. The insufficiency of novelty and inventive step may be established either through evidence that there was disclosure by publication or prior public use: proof of prior public use was a key point in this case. This paper will discuss how to prove prior public use as well as other evidentiary issues during the invalidation procedure by stepping through the aforementioned case.

Contents

I. Case History

II. Evidence Submitted by Schneider Electric

III. Publication Date of Published Documents

IV. Prior Public Use

V. Conclusion

I. Case History

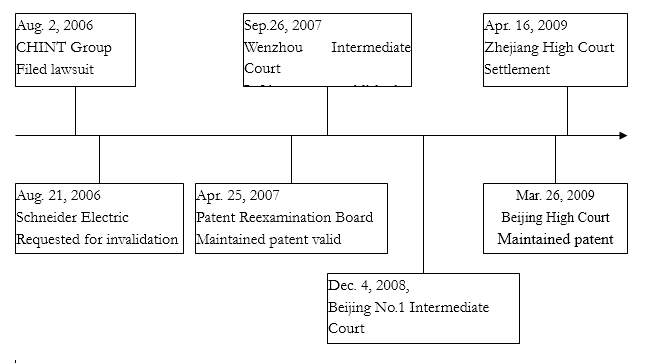

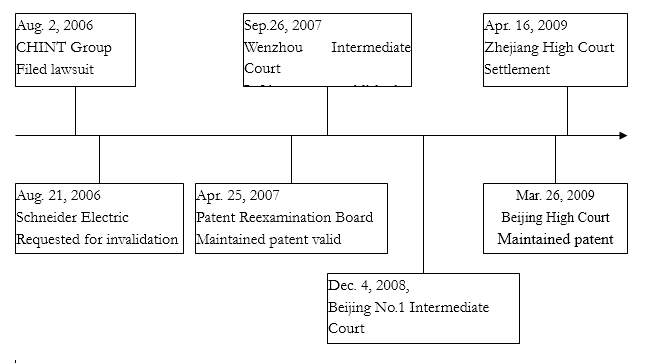

1. Time Chart of The Infringement Litigation and Invalidation Procedure

2. Information of The Patent at Issue

Title of the Patent for Utility Model: a miniature circuit breaker with high breaking capacity

Patent No.: 97248479.5

International Patent Classification: H01H 71/50, H01H 73/00

Patentee: CHINT Group Corp.

Petitioner Filing the Request for Invalidation: Schneider Electric Low Voltage (Tianjin) Co., Ltd.

II. Evidence Submitted by Schneider Electric

After filing the request for invalidation on August 21, 2006, Schneider Electric submitted supplementary evidence six times on September 20, September 21(four times) and November 13 subsequently. In total, 25 pieces of evidence were submitted, which can be classified into six groups. Among these evidences, Group 1 (Evidence 2 to 4), Group 3 (Evidence 11 to 13) and Group 5 (Evidence 19, 20, 24) were used to assess the novelty and inventive step of the patent at issue. As for other evidence, Schneider Electric made no explanation on how to use them in the invalidation case.

There are two issues involved:

(1) The time limit for submitting supplementary evidence;

(2) Should the evidence without any explanation on how to use them be considered when a decision being made.

Regarding to the above issue (1), supplementary evidence may be submitted within one month from the date when the request for invalidation is filed according to relevant provisions of the Implementing Regulations of Chinese Patent law and Guidelines for Examination. Supplementary evidence submitted after the expiration of the time limit, however, may be disregarded by the Patent Reexamination Board. Where the evidence is in foreign language, the time limit for submitting its Chinese translation shall also be within one month from the date when the request for invalidation is filed.

In this case, the supplementary evidence submitted by Schneider Electric on September 20 and 21 should be accepted as they were submitted within one month from the date when the request for invalidation was filed (August 21). The supplementary evidence submitted on November 13 was a Chinese translation of foreign language evidence in Evidence 10 to 17. Although the Invalidation Decision indicates that this evidence was not rejected due to being beyond the time limit, a rejection would have been likely had CHINT Group opposed its entry, which would thereby have resulted in the rejection of all the foreign language evidence concerned in Group 3 (Evidence 11 to 13). The result will be disastrous: Group 3 would have been deemed not to have been submitted due to its Chinese translation had been rejected. That is, even if the evidentiary value of the documents in Group 3 should be enough to prove prior public use, they would have been excluded because their Chinese translation was deemed not submitted.

With respect to the above issue (2), i.e. should the evidence without any explanation on how to use them be considered when a decision being made, it is explicitly prescribed in the Guidelines for Examination that such evidence will not be taken into consideration. The rationale for this is to prevent the petitioner from unfairly surprising the defendant during an oral hearing. As such, the revised Guidelines for Examination in July, 2006 prescribe that the evidence whose relevance is not explained concretely will not be taken into consideration. In addition, based on the same grounds, evidence is unlikely to be taken into consideration in any of the following circumstances:

the petitioner uses one part of a cited reference to assess inventive step when the request for invalidation is filed, while he alleges to use a different part of the same reference to assess inventive step during the oral hearing (new part of the same reference);

the petitioner uses reference 1 as the closest prior art to assess the inventive step by combining with reference 2 when the request for invalidation is filed. However, he uses reference 2 as the closest prior art, combining it with reference 1, to assess the inventive step during the oral hearing (new way of combination);

in cases where only a partial translation of evidence in a foreign language is submitted when the request for invalidation is filed, while the petitioner relies on non-translated portions of the evidence during oral hearing (use of non-translated portion of evidence in a foreign language).

III. Publication Date of Published Documents

Among the evidences of Group 3 submitted by Schneider Electric, the publication date of Evidence 11 is of key importance. Evidence 11 is a brochure for a product – this may be contrasted with other type of published documents such as books, journals and newspapers. When a product brochure is submitted as evidence, the Patent Reexamination Board is relatively strict in determining the publicity or publication date and will frequently require the petitioner to submit other corroborating evidence such as the evidence related to the time when the brochure was printed.

In Evidence 11, the claimed publication date of “26/11/96 16:54” was not printed together with other parts of the brochure. Instead, it resembles a date on a fax. In order to corroborate this date, Schneider Electric submitted Evidence 12, which states that it was “exhibited on Nov. 26, 1996”. However, this statement does not sufficiently corroborate the claimed publication date, “26/11/96 16:54”, in Evidence 11. Furthermore, there is no one-to-one correspondence between Evidence 12 and Evidence 11 since the model number of the product in Evidence 12 is C60, which has multiple types, including C60L, C60N, C60H, etc, while the model number of the product in Evidence 11 only concerns C60N. Based on the above grounds, the publication date of Evidence 11 was not determinative and thus the evidence in Group 3 was not used to assess the novelty and inventive step.

Determining the publication date of published documents is relatively difficult if such documents are those other than books, journals or newspapers, particularly when they are published overseas. Usually, evidence can be collected in the following ways:

(1) Documents retained by libraries. If a document is in a library’s collection, you only need to copy this document from the library. This provides an additional benefit since libraries tend to record the date they obtained a particular document through the use of a seal. Such a date may be deemed to be the publication date. If the library does not use such a system, other means will have to be used to ascertain the date in which the document entered the library’s collection.

(2) Evidence establishing when a document was printed, such as the printing contract, internal documentation of payment, receipts, samples, and date of delivery. It is necessary to note that each piece of this evidence must correspond with one another in order to form a complete evidence chain. Otherwise, as in this case where Evidence 12 involved several types, while Evidence 11 only involves one type, no one-to-one correspondence will be found, and it will be therefore difficult to form a complete evidence chain.

Obtaining evidence of the actual printing date of a document is based on such an assumption that the printing date is considered as the publication date. This assumption conforms with the provisions of Guidelines for Examination, although there are exceptions. For example, the printing date cannot be used as the publication date if there is evidence of the actual publication date which runs contrary to what would be inferred from the date it was printed. This exception is explicitly stated in the Guidelines for Examination and is also reflected in the Invalidation Decision No. WX11880 made by the Patent Reexamination Board.

(3) Other indirect evidence. In this case, Schneider Electric focused its attention on the date stamp

“26/11/96 16:54” in Evidence 11. However, it could have sought other types of evidence such as evidence of the date the document was printed, which may have been admissible despite the fact it was not printed directly on Evidence 11. For instance, in this case, the advantage of this approach lies in that it is otherwise difficult to be determined if “26/11/96 16:54” in Evidence 11 corresponds directly with “exhibited on Nov. 26, 1996” in Evidence 12. It would be easier to determine if Schneider Electric claims that “exhibited on Nov. 26, 1996” in Evidence 12 means that the printing date is at least prior to the exhibition date of Nov. 26, 1996.

The above evidence ((1) to (3)) may be used to prove the publication date. As Evidence 11 involves published documents other than books, journals or newspapers, its publicity will have to be established in addition to its publication date. Like the publication date, others evidence will also be required to corroborate the publicity of a document. The types of evidence enumerated above in (1) to (3) can also be used to prove the publicity.

IV. Prior Public Use

Of the evidence submitted by Schneider Electric, Group 5 was also used to prove the prior public use. The logic of Schneider Electric proving the prior public use is: Company A imported products from Schneider Electric → Company A sold the products to Company B à both importing and selling occurred prior to the filing date of the involved patent à they constituted prior public use.

In accordance with the provisions of Guidelines for Examination the act of importing a product may constitute prior public use. However, the evidence submitted by Schneider Electric was obviously inadequate. The degree of evidence required to prove-up the importation of a product is governed by very explicit provisions in the Guidelines for Examination. They are (1) evidence of importation must be sufficient to prove that said imported product has completed the customs procedure and was released; and that (2) the date of release by Customs is regarded as the publication date for the imported product. Thus, one is normally required to submit a customs declaration that indicates the imported product was released as well as the date of release (see Invalidation Decision No.WX9741 made by the Patent Reexamination Board on April 25, 2007).

Schneider Electric, however, failed to submit the requisite evidence, the customs declaration. Thus even if importation can be shown, it is still difficult to prove that that importation had been completed by a particular date and would constitute prior public use on that date. Although the evidence submitted by Schneider Electric could be used to establish that prior public use occurred through both the act of importing as well as selling the product, the inadequacy of evidence establishing importation foreclosed the alternate use of the evidence. Thus, the evidence that would directly prove importation could have become corroborative evidence which indirectly proves the sale of the product. Both the object of proof and probative force are weakened, which is regrettable.

In order to prove importation, Schneider Electric further submitted notarized witness testimony of the importation. However, in practice, the probative force of witness testimony is relatively weak, despite the fact that it was notarized. The reason is that though the witness testimony has been notarized, it can only establish what the witness has said in front of the notary instead of establishing the veracity of the witness’ statements. In addition, the testimony by a business entity is more likely to be admitted if compared with the testimony made by natural person. Unfortunately, Schneider Electric submitted only the testimony made by natural person.

With regard through using the sale of goods to establish prior public use, although there is no provision on to what degree evidence is required, some guidance may be obtained by examining prior Invalidation Decisions by the Patent Reexamination Board (e.g. WX11407, April 11, 2008). Generally, one must establish (1) the occurrence of the sale; (2) the date the sale was completed and; (3) detailed structure of the product being sold.

Ordinarily, the sales contract is used to prove both the fact that the sale occurred as well as its date of conclusion. Besides the sales contract, it is also necessary to submit other evidence including the seller’s dispatch list, the purchaser’s order list, the purchaser’s payment voucher, the seller’s invoice, etc. Some Invalidation Decisions made by the Patent Reexamination Board indicate that the seller’s issuance of an invoice is deemed to be the completion of the sale with the date of issuance of the invoice being the date of completion.

In this case, although Schneider Electric submitted the seller’s invoice, the fact of the sale was not established since Schneider failed to indicate with adequate precision what product (more specifically, the detailed structure of the product) was being sold. Schneider Electric submitted two pieces of evidence related to what was being sold with one being the appendix to the sales contract, and the other being the photographs taken during the dismantlement of product. Unfortunately, the appendix to sales contract could not be established as corresponding with the sales contract (which may have been possible had they both had the same contract number). On the contrary, even the titles of both contracts were inconsistent and they were barely taken into consideration by the Patent Reexamination Board. As for the photographs, their authenticity was not in question as the process of taking the photographs had been notarized. However, there was still no direct link since the photographs can only establish what was being photographed, not that the photographed product was that which was sold. That is to say, it also must be shown that the product being photographed is or is identical with the product which was sold. In order to prove this point, Schneider Electric submitted notarized witness testimony. However, this witness testimony was not admitted and as a result, Schneider Electric therefore failed to prove that the product incorporating the patents at issue was the product that was being sold.

Ⅴ. Conclusion

This case involves several issues related to the use of evidence during the invalidation procedure, including the time-frame for introducing evidence, methods of establishing the authenticity of the notarized witness testimony, methods of proving-up the publication date and publicity, proving up the act of importation and sale, etc. Each issue may be summarized as follows:

1. Time-frame for introducing evidence. Any additional evidence submitted more than one month from the date the request for invalidation was filed may not be considered.

2. Authenticity of the notarized witness testimony. It is necessary to distinguish what will be notarized (what the witness has said) and what the object of proof is (whether the witness’s words are true), as they may sometimes diverge. The same is also true for the notarization of cyber evidence (i.e., evidence corrected from Internet): what could be notarized is that a statement has been made electronically (e.g. “sold product A on May 1, 2009”), while the object of proof is whether the content itself is true (e.g. whether product A was indeed sold on May 1, 2009).

3. The proof of publication date and publicity. Several pieces of evidence which have one-to-one correspondences with one another are required to corroborate the publication date and publicity. The Patent Reexamination Board is relatively strict in this point.

4. The proof of importation. One must prove that the product at issue has passed through customs and was released. The date of release by the Customs is regarded as the publication date for the imported product.

5. The proof of sale. Proof of sale is established by showing evidence of the sale itself, the date of the completion of the sale, and evidence showing detailed structure of the product being sold. The first two may be established with the sales invoice.

(2009)